The Canadian Bill of Rights was the country’s first federal law to protect human rights and fundamental freedoms. It was considered groundbreaking when it was enacted by the government of John Diefenbaker in 1960. But it proved too limited and ineffective, mainly because it applies only to federal statutes and not provincial ones. Many judges regarded it as a mere interpretive aid. The bill was cited in 35 cases between 1960 and 1982; thirty were rejected by the courts. Though it is still in effect, the Bill of Rights was superseded by the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms in 1982.

Shortly after the First World War was declared, the federal government passed the War Measures Act. The Act gave the government the authority to deny people’s civil liberties, notably habeas corpus (the right to a fair trial before detention). As a result, more than 8,500 people were interned during the First World War and as many as 24,000 during the Second World War — including some 12,000 Japanese Canadians. (See also Ukrainian Internment in Canada; Internment of Japanese Canadians.)

In response to the labour unrest that culminated in the Winnipeg General Strike in 1919, the federal government adapted part of the War Measures Act (specifically Order-in-Council 2384) to add Section 98 to the Criminal Code. Section 98 was in effect from 1919 to 1936. It broadened both the Criminal Code’s definition of sedition and the federal government’s authority to deport people.

In 1932, the civil liberties subcommittee of the Canadian Bar Association recommended entrenching key rights into Canada’s constitution. The recommendation did not lead directly to changes, but it inspired other advances.

Internees being marched off to dinner at the Petawawa internment camp during the First World War.

In 1933, a new political party called the Co-operative Commonwealth Federation (CCF), which eventually became part of the New Democratic Party (NDP), issued the Regina Manifesto. Written after the First World War and during the Great Depression, the manifesto countered what CCF members saw as the excesses of a capitalist system. In its place, the CCF wanted to create a planned socialized economy. The Regina Manifesto also called for basic rights and freedoms, such as government-funded health care; unemployment insurance; old-age security; the right to unionize; and increased spending on public housing.

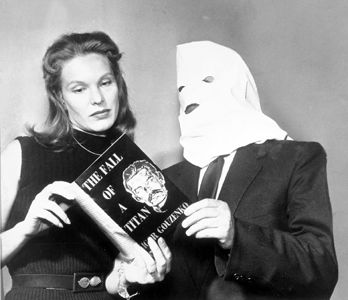

In 1946, Canada’s federal government again suspended civil liberties through the War Measures Act during the Gouzenko Affair. Igor Gouzenko was a Russian cipher clerk working at the Soviet embassy in Ottawa. In September 1945, he defected from the Soviet Union and gave secret documents to Canada. The government used the National Emergency Powers Act to suspend habeas corpus so that it could further investigate espionage in its midst. (See Igor Gouzenko Defects to Canada.)

Igor Gouzenko on television, 1966. Over half of the convictions under the Official Secrets Act were a result of Gouzenko's defection.

James Lormier Ilsley, then the minister of justice, argued that the government was right to suspend civil liberties. “Those principles resulting from Magna Carta, from the Petition of Rights, the Bill of Settlement and Habeas Corpus Act, are great and glorious privileges,” he said. “[B]ut they are privileges which can be and which unfortunately sometimes have to be interfered with by the actions of Parliament.” (See also Magna Carta.) Ilsley saw a bill of rights as something that would limit Parliament’s power. He also thought it would make Canada more like the United States. Parliamentary committees investigated a national bill of rights three times between 1948 and 1950; they rejected it each time.

In 1947, Saskatchewan passed the Acts to Protect Certain Civil Rights — the first bill of rights in Canada. It protected freedoms of conscience, expression, association, freedom from arbitrary detention, and rights to elections, employment, education and property. It also barred citizens from discriminatory restrictions, such as keeping people of a certain “race, colour, creed, religion or nationality” from using a service or establishment. The Act built on Ontario’s 1944 Racial Discrimination Act, which barred citizens from publishing discriminatory restrictions for services or establishments.

Eleanor Roosevelt holding the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, Lake Success, 1949. Canadian John Humphrey was the principal author.

In 1948, the United Nations created its Universal Declaration of Human Rights. Its goal was to prevent a return to the mass killings and destruction of the Second World War. The declaration countered the totalitarian thinking of countries like Nazi Germany by emphasizing the “inherent dignity” and “equal and inalienable rights of all members of the human family” as critical to bringing peace, justice and freedom to the world.

The declaration said every person is entitled to the rights and freedoms and cannot be excluded on grounds of race, colour, sex, language, religion, political beliefs or place of birth. It banned enslavement, torture, and arbitrary arrest and detention. It also enshrined the right to be presumed innocent, and the right to work, among others.

Canadian John Humphrey was director of the UN’s division on human rights. He and his team created the declaration with Eleanor Roosevelt, the United States’ representative to the UN commission on human rights. Canada and most other UN members adopted the declaration in December 1948. (See also Editorial: John Humphrey, Eleanor Roosevelt and the Declaration of Human Rights.)

John Diefenbaker, a lawyer and politician from Prince Albert, Saskatchewan, became one of Canada’s great national champions for civil rights. He began drafting a bill of rights in 1936 as the leader of the Saskatchewan Conservative Party.

Diefenbaker entered the House of Commons in 1940 as MP for Lake Centre in Saskatchewan. He made the case that Canada needed a bill of rights to guarantee “fundamental political, constitutional and personal freedoms.” Opponents to such a bill argued that Canada had not fallen under totalitarian rule during the Second World War and so already had such a guarantee. Diefenbaker pointed to the UN declaration and to all the democratic countries that had since adopted similar bills. He argued that Canada needed a bill of rights to keep people from becoming second-class citizens due to colour, creed or racial origin. He particularly cited discrimination against French Canadians, Indigenous peoples, Métis and European immigrants.

Diefenbaker became prime minister when his Progressive Conservative Party won the federal election on 10 June 1957. Enacting the Canadian Bill of Rights in 1960 became one of his central accomplishments.

John Diefenbaker, prime minister of Canada from 1957-1963.

The preamble of the Canadian Bill of Rights declares that Canada “is founded upon principals that acknowledge the supremacy of God, the dignity and worth of the human person and the position of the family in a society of free men and free institutions.” It also affirms that people and institutions remain free only when freedom is founded on respect for moral and spiritual values and for the rule of law.

The Bill, still in effect, applies only to federal laws and government actions. This is because the requisite provincial consent was not obtained. The Bill recognizes the rights of individuals to life, liberty, personal security, and enjoyment of property. (It does not recognize “possession” of property, since that is a matter of provincial jurisdiction.) Being deprived of these rights is forbidden, “except by due process of law.”

The Bill protects rights to equality before the law and ensures protection of the law. It protects the freedoms of religion, speech, the press, and of assembly and association. It also guarantees legal rights such as the rights to counsel and a fair hearing. Laws are to be constructed and applied so as not to detract from these rights and freedoms.

Diefenbaker’s government also repealed part of the Canada Elections Act to extend the right to vote to Indigenous peoples in Canada. Before that, Indigenous people had to give up their Indian status to vote federally, a trade many were not willing to make.

In the Drybones case, the Supreme Court of Canada rendered a section of the Indian Act “inoperative” and no longer in effect because it violated the Canadian Bill of Rights section guaranteeing equality before the law. The case was about an Indigenous man who was arrested in Yellowknife for violating a section of the Indian Act prohibiting Indigenous people from being intoxicated off their reserves. He and his lawyers argued that violated the Bill of Rights, as a non-Indigenous person could not have faced the same charge. The Supreme Court ultimately agreed, citing the Bill of Rights ban on punishing people on the grounds of race. Parliament later repealed that section of the Indian Act.

However, this success was not the norm for challenges based on the Bill of Rights. The Bill was cited 35 times in court cases between 1960 and 1982; thirty were rejected. The Drybones case was the only one to change a law.

The Bill of Rights applies only to federal laws and government actions, because provincial consent was not obtained. For example, the Bill does not recognize “possession” of property, since that is a matter of provincial jurisdiction. Another of the Bill’s weaknesses is that many judges regarded it as a mere interpretive aid. Section 2 says that Parliament can override the mentioned rights by inserting a “notwithstanding” clause in the applicable statute. This was done only once — during the 1970 October Crisis. (See also Notwithstanding Clause.)

Soldier and child, 18 October 1970, during the October Crisis.

The Bill of Rights was used in the Lavell Case to argue Canadian law violated Indigenous women’s rights. In 1970, an Ojibwe woman, Jeannette Corbiere Lavell, married a non-Indigenous man. Under the Indian Act, that meant she lost her Indian status as she had “married out.” She would lose her status and her children would not inherit it. But Indigenous men who married non-Indigenous women kept their status and could pass it on to their children. (See also Women and the Indian Act.)

After her case was dismissed in 1971, Corbiere Lavell petitioned and won her case in the Federal Court of Appeals later that year. The appeals court judges outlined that the Indian Act did not afford equality to Indigenous women. They recommended that the Indian Act be repealed for failing to adhere to the laws established in the Bill of Rights. However, the Supreme Court of Canada ruled against Corbiere Lavell in 1973. In a controversial and much-questioned decision, it found that the Bill of Rights did not invalidate the Indian Act.

Jeannette Corbiere Lavell (left) and Sharon McIvor (right) speaking at the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights (2012).

Although the Bill of Rights remains in effect, many of its provisions were superseded by the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms in 1982. The Charter is a much broader human rights law. It also has greater power because it applies to both federal and provincial laws and actions. And unlike the Bill of Rights, the Charter is part of the Constitution — the highest law of the land.

The Charter can be limited by the notwithstanding clause, also known as the override clause. Section 33 permits federal, provincial and territorial governments to temporarily bypass Charter rights in section 2 and sections 7 to 15. This means those legislative bodies can override court rulings interpreting the Charter in those areas. The legislative body can exempt such laws for five years. It must then renew the law or let it lapse.